Alejandro Sommer: A dark sky mission in Argentina

Alejandro Sommer, an advocate for dark skies in Misiones, Argentina, works to protect the province's night environment and indigenous cultural heritage through astrotourism and storytelling.

Each month DarkSky International features a DarkSky Advocate from the worldwide network of volunteers working to protect the night. This month we’re highlighting the work of Alejandro Sommer in Argentina.

Lo importante no es encontrar tu estrella, sino en no perderla de vista.

– Alejandro Sommer

The important thing is not to find your star, but not to lose sight of it.

Alejandro Sommer is full of energy. You could say he’s a man on a mission to protect the darkness of his province: Misiones, Argentina. The second smallest of the country’s 23 provinces, Misiones is Argentina’s opposable thumb, a little finger of dark sky bordered by the blazing lights of Paraguay and Brazil to the west and north.

“If you look at the light pollution map, you will see Brazil and Paraguay fully lighted and Misiones is a dark-sky corridor,” says Alejandro. “I am really trying to protect that.”

DarkSky Advocate, astrotourism consultant, cultural cosmologist, dark sky storyteller, and teacher, Alejandro wears many hats and exudes relentless enthusiasm for his work. His main passion is Cielo Guaraní (Guaraní Sky), an astrotourism project at Salto Encantado Provincial Park that connects visitors with the cosmology and culture of the local indigenous communities, the Guaraní, through storytelling and nighttime excursions into the jungle of Misiones.

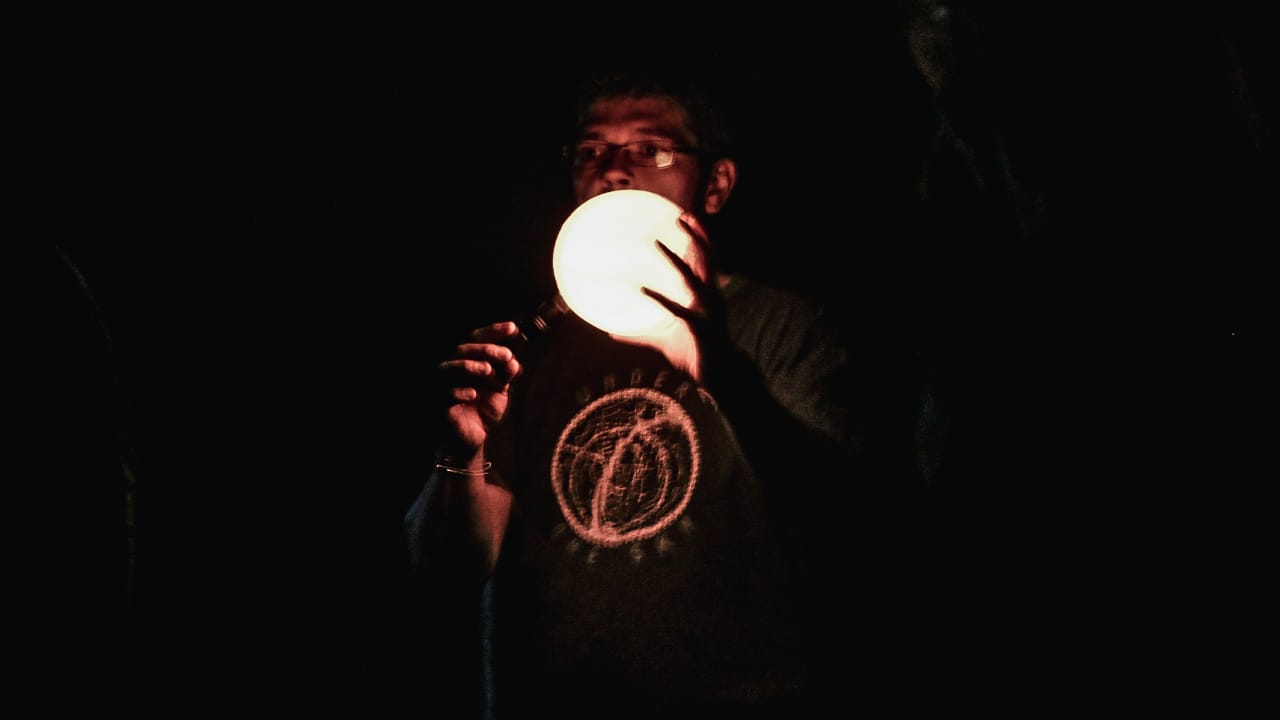

“According to Guaraní tradition, people are not allowed into the jungle at night because of bad spirits. But if you have the protection of tacuaras or takua recha (bamboo torches), you may enter. We do a ritual blessing and ask nature’s permission to be there. It works perfectly because I need red light to do modern astronomy, so we replaced the red light with safe, controlled fire, which is already part of the Guaraní rituals. It’s lovely.”

Alejandro also works on a pre-Hispanic cultural project disseminating the legacy of the Jesuit astronomer Buenaventura Suárez, who lived in Misiones in the late 17th century.

In addition to all of this, Alejandro is a trained Galileo Teacher, teaching inclusive astronomy to visually impaired students; and in his spare time, he leads a scout troop.

Alejandro’s involvement in the dark-sky movement in Argentina led him to begin advocating for government policies to protect Misiones’ delicate nocturnal environment. Earlier this year, Misiones adopted a provincial law for dark-sky protection according to DarkSky lighting principles. A major win for nocturnal conservation in Argentina, the law goes beyond the protection of nature reserves to include a full provincial lighting management plan that covers cities and urban areas, too.

Alejandro emphasizes the importance of collaborating with the indigenous community and promoting and preserving their unique astronomical cultural heritage. The Cielo Guaraní visitor experience includes a collaborative myth and storytelling session with several indigenous leaders and chiefs, including Fernando Villalba from the Aldea Peruti community and, more recently, Domingo Moreira from the Aldea Yvytu Porá community.

During the pandemic, Cielo Guaraní has focused on attracting domestic visitors to Misiones, many of whom, Alejandro says, have never experienced a truly dark sky. The project is one of eight stops on a new national astrotourism route through Argentina — the Ruta de las Estrellas (Route of the Stars).

“This is the only place [in Argentina] that the public can have outdoor access to the stars and look through a telescope to see a very good sky. So that really is a big goal,” says Alejandro.

Alejandro’s plan for Misiones over the next few years is to see the implementation of the new light pollution law, which stipulates that an DarkSky representative must sign off any commissioned changes to lighting in the province. Further developments include three new regions oriented to astrotourism, additional light pollution mapping, creation of more astrotourism products, and consolidating the protected natural areas and ecotourism activities across the province, which in 2019 was listed as Argentina’s capital of biodiversity.

He also has designs on light protection work in neighboring Paraguay, which has been stalled by COVID-19. “I have Paraguay right there — 10 blocks away, the Paraguay River and one border — and I can’t cross because of the pandemic situation. I have a huge consultancy project on light policy there, and I just can’t go. So, like all of this work, it will take time, but I will get there.”

The most important thing to Alejandro, though, is to continue creating awareness about the cultural heritage of the Guaraní.

“We cannot leave aside the wisdom of the worldview, cosmology, and teaching of the Guaraní people. They have been the custodians of nature since ancient times.”

The Guaraní legend of the hummingbird

Below we have included the Guaraní legend of the hummingbird, a very sacred bird for the community. Visitors to Cielo Guaraní hear this legend told by torchlight by Domingo Moreira, chief of the Aldea Yvytu Porá community.

One day, the jungle began to burn in flames. All the animals fled in a stampede except one small hummingbird. He seemed a little more scared and desperately tried to get closer to the flames and then returned to the bank of the Paraná River to cool off. His intention of reaching the fire seemed to have no sanity. A jaguar saw the hummingbird trying to fly into the flames and, very concerned, told him to stop, and not to return to his house because the fire could not be put out. The little hummingbird told the jaguar that he was not trying to get to his house, but that on each trip to the Paraná River, he brought all the water he could carry and threw it onto the fire. The jaguar told him, “But no! You cannot extinguish it!” The hummingbird replied, “Maybe I can’t extinguish it, but I’m doing my part to take care of my home.” After hearing this, all the animals began to do the same and fought for their home until they could tame the fire.