Q&A with DarkSky Delegate Michelle Wooten from Alabama, USA

Dr. Michelle Wooten, an astronomy educator and president of DarkSky chapter Starry Skies South, discusses her work in protecting the night sky and raising awareness about the detrimental effects of light pollution in the Southeastern United States.

Each month DarkSky International features a DarkSky Advocate from the worldwide network of volunteers who are working to protect the night. This month we’re highlighting the work of Michelle Wooten from Birmingham, Alabama, United States.

We recently spoke with Assistant Professor of Astronomy Education at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Dr. Michelle Wooten, about her work as an educator whose passion for the night sky goes beyond studying it — she wants to protect it. As president of the DarkSky chapter Starry Skies South, she works to spread awareness of the harm light pollution is doing to the Southeastern United States.

Q: What got you interested in protecting dark skies?

A: I am an astronomy educator. My original interest in protecting dark skies came from a desire to support students in using their astronomy knowledge toward sustainable development of their community. Over time, my interest in protecting dark skies has only deepened as I’ve learned about the effect of artificial light on my own health, environmental health, and students’ ability to see and enjoy the stars.

Q: Can you tell us about dark skies in the Southern US? What are the opportunities and challenges?

A: In my experience, people in the southeast love the beauty of this place. The local State Parks saw a significant uptick in use during the pandemic. We are hoping to capitalize on this interest in the outdoors with our work. Most of our strategizing is based in our city and state contexts, but we have some shared context from the standpoint of centralized electrical power.

Opportunities

- Educational Outreach: We are so lucky that our local State Parks, Science Centers, and Museums have been excited to partner with us on educational initiatives. Several new applications of Dark Sky Places are also in the works.

- Partnerships: I am also surprised by how easy it is to get connected with the lead personnel of other environmental advocacy groups — like the Audubon Society, the Riverkeeper Associations, and State Park educators. I seem to know most of them by name in the Birmingham area, even though it is my first year here. Some say making environmental-advocacy connections is easy here because there are so few of us focused on it. However, I would temper that claim with what one’s position title and purview leverages us in making these connections.

- Novel News Entries: Some members of the new DarkSky Chapter Starry Skies South, like Tom Berta (South Carolina) and Marlena Wald (Georgia) have had great success publishing letters to their newspaper’s editorial staff or presenting on their advocacy efforts on television news.

Challenges

- Lack of Awareness: Most people I teach or meet during outreach events, even some astronomy clubs, have never heard or thought about light pollution. They are sincerely interested and want to know more. When students in my courses interview their friends and family members about light pollution, some students report scoffing at the idea of light “pollution”, as either not real or not important. Because of this, I often use the term “artificial light at night” rather than “light pollution.”

- Equity in Access: Some of the darkest, public places are potentially not safe, especially for persons of color. Drew Lanham in his book The Home Place, and several amateur astronomers’ experiences at specific locations across Alabama, have put this consideration in perspective for me. We want to make sure everyone feels welcome and comfortable at the dark sky locations we also aim to protect.

- Resistance toward Legislation: The Southeastern states have deeply entrenched cultural values around individual liberty. One consequence is that legislators can be hesitant to impose restrictions, such as lighting ordinances, on their constituents. To learn more about these issues, I recommend the free, online documentary-shorts Southern Exposure Films. Still, environmental advocacy groups, like the Riverkeepers, have had exceptional successes working with the public to come up with solutions that best serve the people and protect our wonderful environment for future generations.

- Trees: Yes, trees. It can be very challenging to find enough cleared land in dark sky locations to see the stars. I find this particularly ironic because trees are the reason I wanted to move back to the Southeast, after living most of my career elsewhere.

Q: Tell us about your new DarkSky Chapter, Starry Skies South. Why did you start it?

A: In the same way that I want to support students to make positive changes in their community, I wanted to use the leverage of my position, as an astronomy professor, to support positive community change more broadly. When I started attending meetings for my local astronomy club, the Birmingham Astronomical Society, I learned that some members were interested in dark sky advocacy but just needed support in organizing an effort. That’s when I started reaching out to astronomy clubs across Alabama and giving presentations on light pollution — with an embedded invitation to join a dark sky advocacy collective. Ultimately my goal is to support vibrant connections and collaborations between students and community members that are focused on preserving a healthy, sustainable, starry nighttime environment.

Q: What would you tell others who may be interested in starting a Chapter in their area?

A: Firstly, it is clear that others are looking for someone to lead this effort. Try to be okay with making executive decisions, but also making ample opportunity for input. I put the big things up to majority vote: our name, our meeting time, our non-profit paperwork wording; and I take care of the small things — like drafting our monthly meeting agenda. During our meetings, I make space to recognize the many good efforts that our members are making. We really find inspiration from one another, even when we feel limited on what we can achieve due to personal or systematic constraints.

Q: As a formal educator, how do you integrate dark sky education in the classroom?

A: One step at a time! There is so much I want to do but cannot due to time constraints. To write one good assignment takes a lot of research into the local context, how students will actuate the assignment, and how the assignment fits in the broader curriculum.

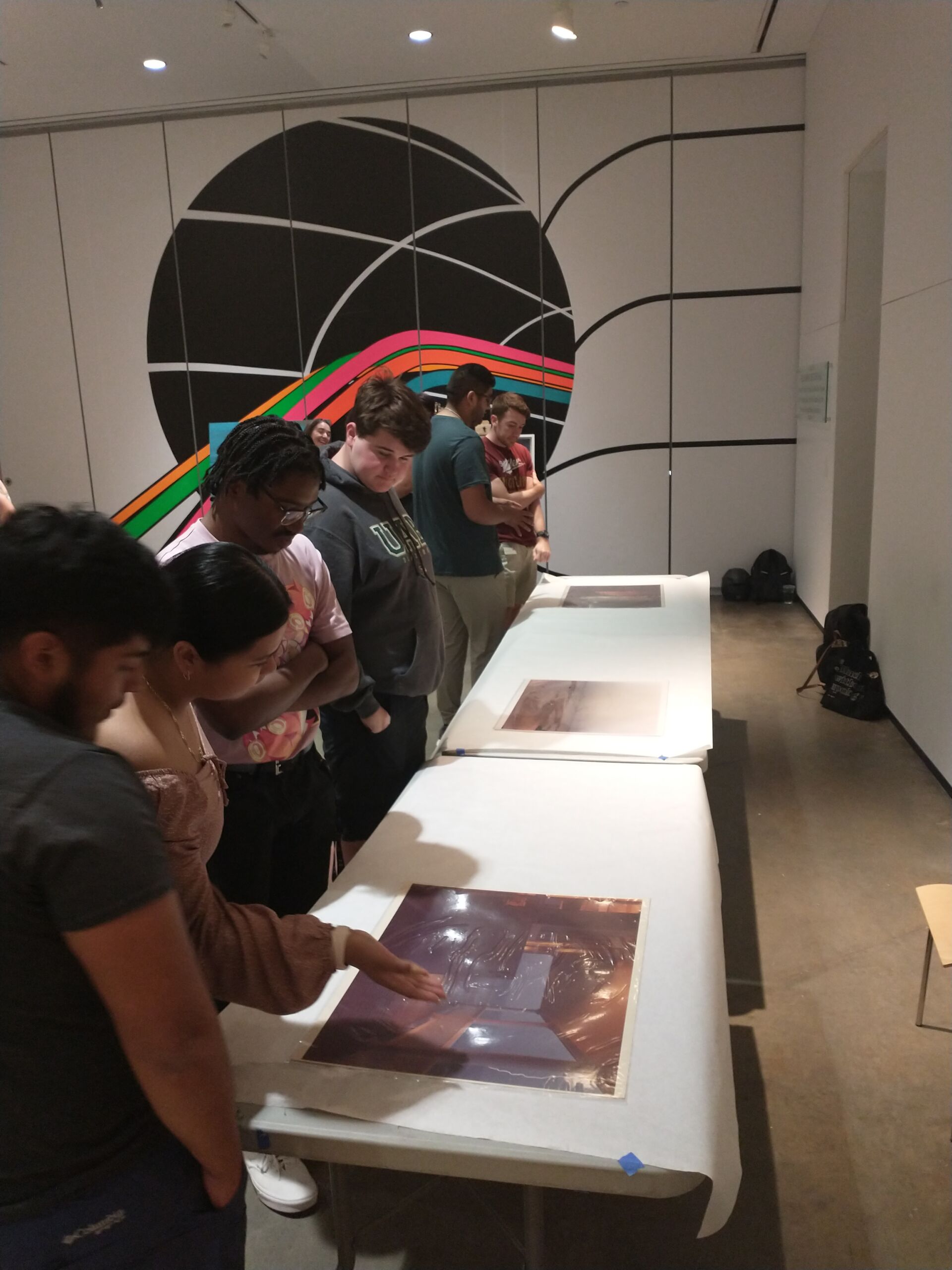

I started by incorporating Globe at Night as a lab assignment. Then I reached out to other dark sky advocates who are also formal educators (like Diane Turnshek, James Lowenthal, and Daniel Mendoza) for ideas. A recent assignment was inspired by last year’s (2020) annual DarkSky International conference presenter, Malaysian artist Nurul Syahirah Binti Nazarudin. She discussed art as a way to support people’s expression of their delight in and connection to dark, starry skies. And so now in each class I teach, I have at least one art assignment focused on students’ or other cultures’ connection with the night sky. My university is supporting this effort with an annual Astronomy Art Showcase for students to share their work! The inaugural event is on October 11, 2022, from 5 – 6:30 p.m. at ArtPlay in Birmingham, and everyone is invited to attend.

Q: Why are dark skies important to the culture in the southern US?

A: Every semester I assign and read hundreds of student essays reflecting on nature, place, and being Earthen. Having assigned this essay at universities across the United States, like Pennsylvania and Colorado, a unique theme I see in Alabama students’ essays is their pleasure in going back home to rural places, where the skies are full of stars and the wilderness is loud and present. My read is that many people in the southeast are proud about their wild, off-the-grid places. Even non-astronomy colleagues who have grown up in the city describe “disgust” at the recent decades’ diminishing of the visibility of stars. Dark skies are important to the culture in the southern US because of their entanglement with a particular brand of place-based identity.

Q: What resources have been most effective in your dark sky work?

A: I make use of it all: other dark sky advocates, the DarkSky annual conference, and the DarkSky monthly advocates webinar. The webinars are probably the most positive experience I have every month, and I put to use something I learn from every one of them. I would like to especially thank Todd Burlet of Starry Skies North, Bruce McGath of Arkansas Natural Sky Association, Brent and Dawn Davis, Diane Turnshek, and Bettymaya Foott, for providing important insights and support in getting Starry Skies South off the ground.

Q: What is your greatest success in dark sky conservation?

A: Beyond the monthly success of interacting with amazing people across the Southeast during Starry Skies South meetings, my personal favorite success was co-organizing International Dark Sky Week events at local State Parks, planetaria, and observatories. I remember thinking, “If I did one good thing in my life, it was these events.” I felt like the Universe was celebrating with me when on the night walk event at Cheaha State Park, we saw ghost (blue) fireflies. It was epic!

Q: What is your favorite part about the night?

A: I find that the conditions of the night bring me freedom to contemplate, rest, and explore without being simultaneously evaluated for how I am doing these things.

Q: What is your favorite thing to tell people during dark sky events?

A: At dark sky events, I sense less power in what I tell people than in how I engage them. I put into practice research from science education that shows people learn better when they are involved. My presentations are more of a dialogue, inviting people to share their entry into a love of starry skies, putting the new vernacular they learn (glare, trespass, skyglow) to use, evaluating light fixtures for dark-sky friendliness using the 5 Principles of Dark Sky Friendly Lighting, and contemplating steps we can take to make change.

Q: What is the coolest thing you have ever done?

A: My year studying abroad in New Zealand as an undergraduate was very cool. My goal was to learn the stars that are visible from the southern hemisphere. Most folks in the United States cannot see the constellations near the south celestial pole, like Centaurus. Orion looks upside-down, and southern hemisphere cultures have their own stories about the stars. While in New Zealand, I worked as a planetarium presenter at the Stardome Observatory which kicked off my career in astronomy education. During that year, I also performed in front of thousands with a hip hop dance team, won the national choir championship with the City of Auckland Singers, learned how to dance with a poi in a Māori performing arts class, and drove around the East Cape to see the Sun rise from the easternmost point of the country.

Q: Any dark sky jokes to share?

A: I don’t know one, but my spouse would not let me submit this without one, so he made up the following: “Two dark sky advocates walk into a brightly lit bar. ‘Ow!,’ they both said, ‘we couldn’t see it because of the glare.’”

Q: How about a funny story that happened in the dark?

A: I have been watching the night sky closely for a few decades now. While living in Alabama, I have seen things that I just cannot explain, and it is very humorous to me. Like, how many times have I written off students’ accounts of strange things they see in the sky as this or that celestial phenomenon? And now I’m stumped.

Q: Is there anything else you would like to share with us?

A: I take a lot of inspiration from the philosopher Michel Foucault, who wrote, “Believe that what is productive is not sedentary but nomadic.” At first, it seems that having a blueprint for how to do dark sky advocacy, what works and what doesn’t would be ideal. I think that Foucault would see such blueprints as sedentary, taking focus off the myriad ways that dark advocacy can and does happen in communities across the world. Personally, I have found that nomad-ism — building positive connections with others across my communities leads me to increasing faith and confidence in the power of these connections. And these connections multiply as I see others in Starry Skies South doing the same.

For more about what Starry Skies South does, check out their website here!

To join the DarkSky Advocate Network, go here!